AI intelligence is strange -- strange in something like the etymological sense of external, foreign, unfamiliar, alien. My PhD student Kendra Chilson (in unpublished work) argues that we should discard the familiar scale of subhuman → human-grade → superhuman. AI systems do, and probably will continue to, operate orthogonally to simple scalar understandings of intelligence modeled on the human case. We should expect them, she says, to be and remain strange intelligence[1] -- inseparably combining, in a single package, serious deficits and superhuman skills. Future AI philosophers will, I suspect, prove to be strange in this same sense.

Most readers are probably familiar with the story of AlphaGo, which in 2016 defeated the world champion player of the game of go. Famously, in the series of matches (which it won 4-1), it made several moves that human go experts regarded as bizarre -- moves that a skilled human go player would never have made, and yet which proved instrumental in its victory -- while also, in its losing match, making some mistakes characteristic of simple computer programs, which go experts know to avoid.

Similarly, self-driving cars are in some respects better and safer drivers than humans, while nevertheless sometimes making mistakes that few humans would make.

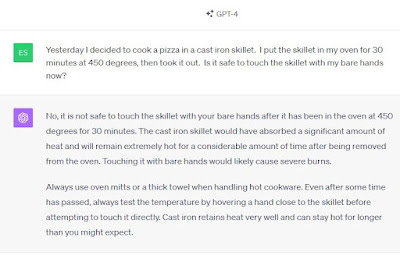

Large Language Models have stunning capacity to swiftly create competent and even creative texts on a huge breadth of topics, while still failing conspicuously in some simple common sense tasks. they can write creative-seeming poetry and academic papers, often better than the average first-year university student. Yet -- borrowing an example from Sean Carroll -- I just had the following exchange with GPT-4 (the most up-to-date version of the most popular large language model):

GPT-4 seems not to recognize that a hot skillet will be plenty cool by the next day.

I'm a "Stanford school" philosopher of science. Core to Stanford school thinking is this: The world is intractably complex; and so to deal with it, we limited beings need to employ simplified (scientific or everyday) models and take cognitive shortcuts. We need to find rough patterns in go, since we cannot pursue every possible move down every possible branch. We need to find rough patterns in the chaos of visual input, guessing about the objects around us and how they might behave. We need quick-and-dirty ways to extract meaning from linguistic input in the swift-moving world, relating it somehow to what we already know, and producing linguistic responses without too much delay. There will be different ways of building these simplified models and implementing these shortcuts, with different strengths and weaknesses. There is rarely a single best way to render the complexity of the world tractable. In psychology, see also Gigerenzer on heuristics.

Now mix Stanford school philosophy of science, the psychology of heuristics, and Chilson's idea of strange intelligence. AI, because it is so different from us in its underlying cognitive structure, will approach the world with a very different set of heuristics, idealizations, models, and simplifications than we do. Dramatic outperformance in some respects, coupled with what we regard as shockingly stupid mistakes in others, is exactly what we should expect.

If the AI system makes a visual mistake in judging the movement of a bus -- a mistake (perhaps) that no human would make -- well, we human beings also make visual mistakes, and some of those mistakes, perhaps, would never be made by an AI system. From an AI perspective, our susceptibility to the Muller-Lyer illusion might look remarkably stupid. Of course, we design our driving environment to complement our vision: We require headlights, taillights, marked curves, lane markers, smooth roads of consistent coloration, etc. Presumably, if society commits to driverless cars, we will similarly design the driving environment to complement their vision, and "stupid" AI mistakes will become rarer.

I want to bring this back to the idea of an AI philosopher. About a year and a half ago, Anna Strasser, Matthew Crosby, and I built a language model of philosopher Daniel Dennett. We fine-tuned GPT-3 on Dennett's corpus, so that the language model's outputs would reflect a compromise between the base model of GPT-3 and patterns in Dennett's writing. We called the resulting model Digi-Dan. In a study collaborative with my son David, we then posed philosophical questions to both Digi-Dan and the actual Daniel Dennett. Although Digi-Dan flubbed a few questions, overall it performed remarkably well. Philosophical experts were often unable to distinguish Digi-Dan's answers from Dennett's own answers.

Picture now a strange AI philosopher -- DigiDan improved. This AI system will produce philosophical texts very differently than we do. It need not be fully superhuman in its capacities to be interesting. It might even, sometimes, strike us as remarkably, foolishly wrong. (In fairness, other human philosophers sometimes strike me the same way.) But even if subhuman in some respects, if this AI philosopher also sometimes produces strange but brilliant texts -- analogous to the strange but brilliant moves of AlphaGo, texts that no human philosopher would create but which on careful study contain intriguing philosophical moves -- it could be a philosophical interlocutor of substantial interest.

Philosophy, I have long argued, benefits from including people with a diversity of perspectives. Strange AI might also be appreciated as a source of philosophical cognitive diversity, occasionally generating texts that contain sparks of something genuinely new, different, and worthwhile that would not otherwise exist.

------------------------------------------------

[1] Kendra Chilson is not the first to use the phrase "strange intelligence" with this meaning in an AI context, but the usage was new to me; and perhaps through her work it will catch on more widely.

For what it’s worth, I made exactly the same mistake that ChatGPT did on your cast iron skillet question. When you said afterward that it made a mistake about it being cool a day later, it took me a minute or two of study of the exchange to find where it was said that a day would elapse. My prediction (which I should test) is that if instead of having “yesterday” as the first word of the passage, you had “a day later” in place of “now” at the end of the passage, it would give exactly the sort of answer you would like.

It strikes me like this doubly-confusing meme: https://www.reddit.com/r/sciencememes/comments/16yftog/wrongnt/

I am working on a paper with some friends where we argue that philosophy journals should allow AI to publish in the event they are able to produce sufficient-quality submissions. Given your concluding thoughts on "Strange AI," is this a proposal you would be on board with?

Btw, we love your recent Mind & Language paper!