I love bad art.

Gather some friends and create some bad music. Cruise in a car covered with graffiti doodles. Hand a five-year-old crayons and free time and see what weirdness emerges.

Something worth celebrating happens. Although the art is "bad" in a one sense -- it will win no prizes and astound no critics -- it wonderfully enriches the world. How?

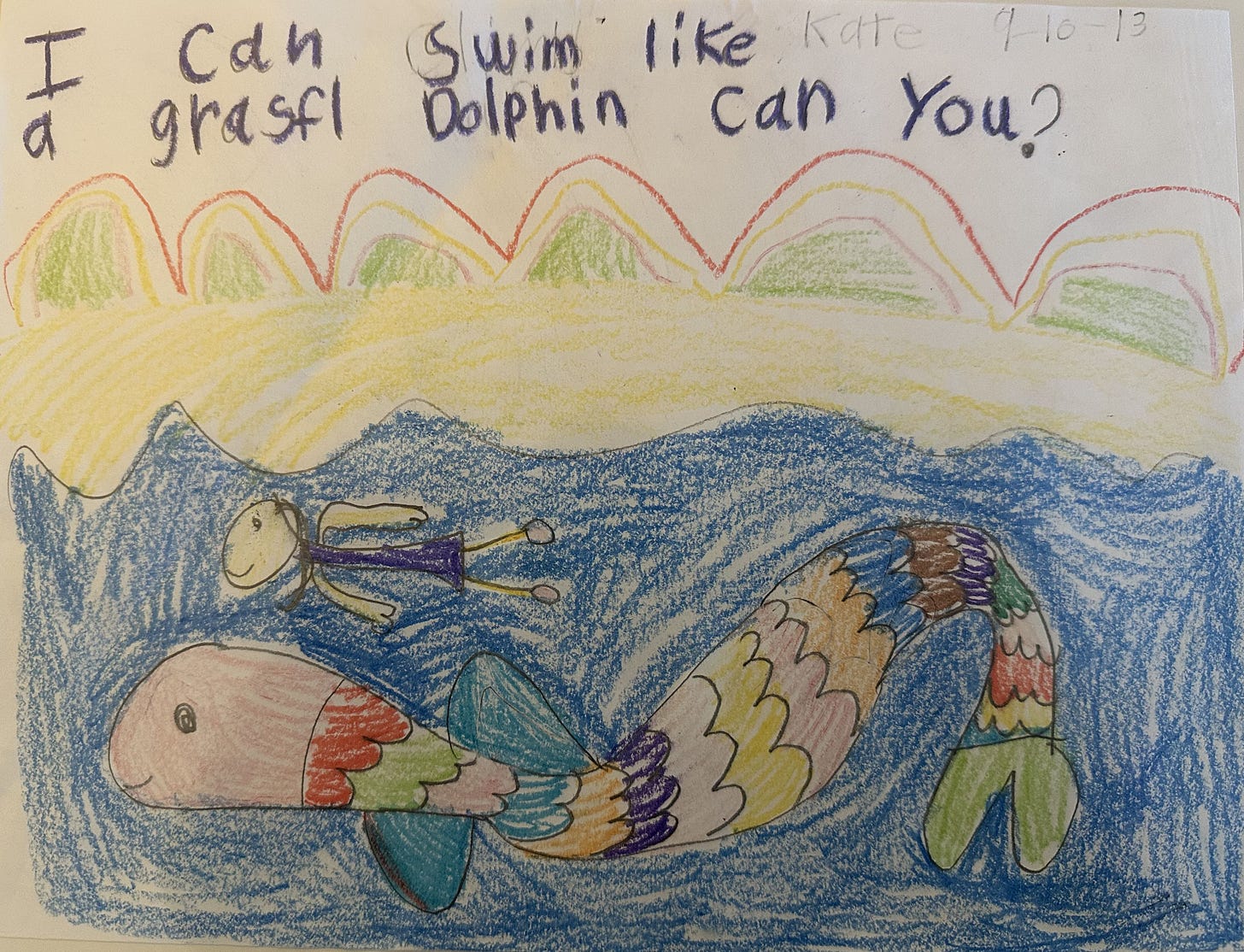

[I can swim like a grasfl dolphin can you? by my daughter Kate, at age six]

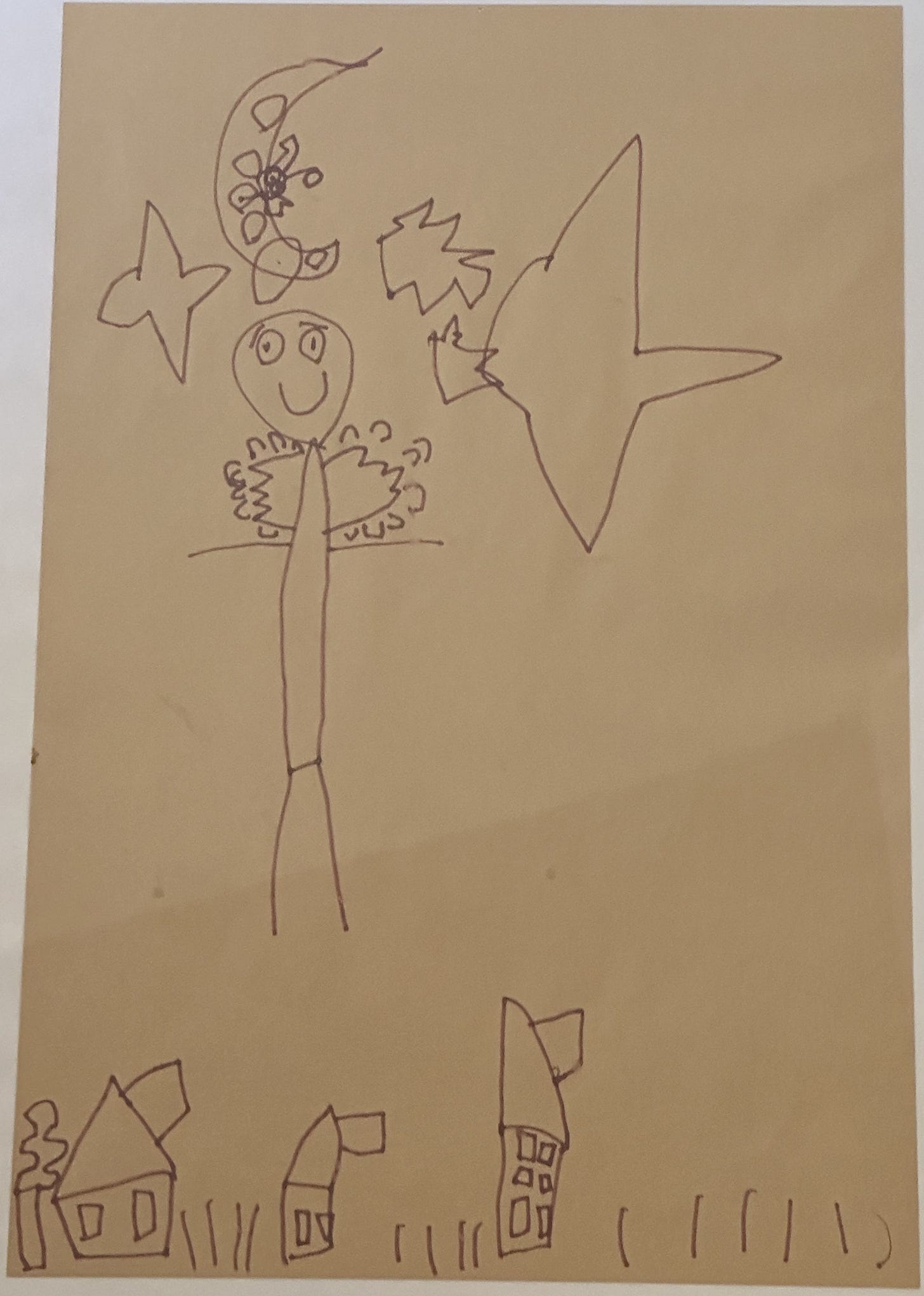

[Angel and moonbug, by my son Davy, circa age five]

The awesomeness isn't due to impressive technique, honed by years of craft, like Rembrandt. It's not due to intrinsic beauty and color-mad insight, like Van Gogh. It's not due to challenging conventional interpretability and the boundaries of artistic tradition, like Picasso.

Nick Riggle argues that art draws most of its aesthetic value from shared aesthetic engagement, and I agree that's some of the sorcery. A Vengefull Kurtain Rods song, a Vogon poem, or a Mystical Anarchist "motorized cathedral" art car is a social act, deriving value from the connections it fosters and the shared practice of aesthetic valuing -- including, in the case of Vogon poetry, the shared practice of aesthetic loathing. Parents and children bond over the child's emerging abilities and tastes.

But I don't think that Riggle has quite struck to the heart of it. When I improvise on the piano alone at home, relishing the quirky turns of my intermediate jazz piano skills, the ghost of my old piano teacher Matt Dennis may hover nearby, but my minor participation in the social tradition of jazz creation is only part of the story. Similarly for grandma painting seascapes in the eldercare facility -- kitschy, flawed, excruciatingly hers. Similarly for the strange abstract doodles I sometimes sketch when bored at a faculty meetings, which I aesthetically enjoy probably more than I should.

It helps to consider why five-year-olds are better artists than eight-year-olds. Eight-year-olds draw conventional stick figures, conventional houses with two neat windows, a door, and a triangle roof with chimney, a standard rainbow, a standard sun. Four-year-olds have only an inkling of these conventions, invent their own weird solutions -- people as heads on towering legs with too many toes, cars that look like falling toast. At five and six and seven, they shape themselves more toward the generic. Kate's swimmer is generic, but her dolphin is wild and long -- and are those hills or waves or rainbows in the background? Davy's houses look standard, but the grass is sunflower tall, the chimneys jut precariously sideways, his angel's wings are small, and he hasn't figured out how to draw conventional nighttime stars.

Preschoolers and early elementary schoolers show more individuality in their art. It dances barefoot across your expectations. Their lines reflect distinctive aesthetic attempts. This distinctiveness is harder to discover in the more conventional art of later childhood and needs to be rediscovered later. Similarly for grandma, if she hasn't consumed too much Bob Ross. If her seascapes are generic, in one sense they are more competent and less "bad" than untrained attempts, but they have less point and are less valuable than a heartfelt effort that finds a different solution.

Bad art manifests the raw signature of the individual eye. It shows a mind grappling with an aesthetic challenge. If the artist judges it a failure and crosses it out, then their vision hasn't been realized. But if it is beloved in its strangeness -- if the creator affirms it as a successful completion of their artistic intention, then it's a distinctive achievement that reflects the mind and hand of the moment.

Our planet -- amazingly, awesomely, wondrously, beautifully, stunningly (to any aliens who might happen upon it amid the dark blandness of space) -- hosts five-year-olds who draw bugs on the moon and six-year-olds who draw impossibly long dolphins, teenagers doodling on cars, friends collaborating on goofy songs. If no one else would have done it the same way, then the work reflects your distinctive aesthetic encounter with the world. It's a piece of you made visible. Especially (but not only) for those who care about you, it's your individual eye, voice, and values that ignite its meaning.

Bad art can fail in two ways: When it's so generic that the artist vanishes or when the artist disowns it as failing to capture their aesthetic vision. If it passes the sibling tests of distinctiveness and affirmation, it is valuable.

A world devoid of weird, wild, uneven, wonderful artistic flailing would be a lesser world. Let a thousand lopsided flowers bloom!

How cool! I enjoyed this article. I'm not in aesthetics, so I'm no expert, but I liked thinking through the idea of "bad art" in this way...

These are my favorite posts that you do Eric. These are the posts which lift you from the humdrum of philosophical illuminatia.

And also, because you tolerate words like philosophical illuminatia